A Work Life Composition – Saga No. 6

[The Summer I loaded trucks at Sears Logistics Center in Manteno, Illinois – June through September 1999]

…

Art school at the community college wasn’t going to pan out for me. As a witless, frumpy shoegazer I flunked most of the general education classes as well as most of the art classes. I just didn’t care about them. Chasing after the wind, I literally couldn’t focus or motivate myself to even show up half the time.

My friend Alex once articulated it best –

“I was planning to come to Two-Dimensional Design class today. But I woke up and realized my TV was working.” (1)

General forces in my periphery, however, did guide the adage that at age nineteen I felt I needed some sort of plan. Cartooning for a living wasn’t to be, and “playing” “bass” in a “punk” ensemble with a “drummer” named Santa Claus wasn’t going to generate any income. I knew very well I needed to be out of my parents’ basement at some respectable point in life.

I held a strange on-again, off-again attachment to my girlfriend, mainly out of fear. God knows I didn’t like her. Poor kid was in grad school and to my feeble understanding of the day, it was some sort of security measure to hitch my wagon to. A master’s degree in social work, no less. I came to my senses, no doubt, but I am stuck with these memories of a time from before my frontal cortex was fully developed. (2)

I made a pivot. In the parking lot after my interview at Sears Logistics Center in Manteno, I ran into an acquaintance who worked there. I asked him if he liked it. He remarked, “Well… you’ll lose a little” signifying to his belly, “and you’ll gain a little…” pointing to his bicep.

To note, this was one of those jobs demanding enough that it alters you physically. Party time was over. My decorative dance card had been pulled. No more leisurely wafting between English 101 and the KCC cafeteria to gingerly munch my chubby boy mozzarella sticks.

In the blazing June of 1999 I quit my five dollar an hour part-time job at Aurelios Pizza. I took an eight dollar an hour full time battlement at Sears Warehouse, loading semi-trucks. Real world shit. I went from rocking scorching hot pizza ovens to baking inside of a metal shipping container – an alternate, scorching hot oven designed to forge human pizzas.

I found I had to get there and park fifteen minutes early just to be able to walk to my punch clock and check in on time. The clock was set at the shipping department in the back of the elongated building. It was so far away I had to adjust my schedule an extra fifteen minutes to get to the punch clock by 6 AM after I was already inside the building where I worked.

To reiterate, if I just showed up on time, I would be fifteen minutes late. That’s the corporate America I’ve grown up in. Not only did these assholes make you punch a timecard like a prisoner entering a yard, but they couldn’t have just put the check-in at the front of the god damn building?

My first day at the warehouse I formed a small crew with three other guys who were in the new-hire training bootcamp with me:

- Samuel, a Spanish-only speaking Latino man with a tear drop tattoo on his face.

The tear drop facial tattoo was filled in, so I understood it to mean that he had killed someone in an act of revenge for that person killing his friend.

- Jesse, a self-diagnosed schizophrenic.

- and, Mark.

Mark wore an Atari Teenage Riot tee shirt multiple days in a row, every week, and had a chin piercing. I knew Atari Teenage Riot because I saw them open for the Smashing Pumpkins the summer before. The summer where I still had hope. Mark was the first dude I ever associated with who had been homeless in the past.

My band. My lunchbreak posse.

We stood in the sad windowless breakroom trying on our flimsy, useless Velcro safety belts we had to wear in order for Sears to not get sued if we pulled our backs out lifting your Christmas treadmill. Clomping around, it was the first time I ever had to put on steel toed shoes. Clanky, cheap, and blister-inducing. As the weeks droned by, they formulated soft art school dropout teenager feet to grizzled working man callous pads.

As a side bar, if you don’t know, steel toed shoes are not really designed to protect the toe from falling objects.

No.

They are designed to sever the toes completely off. The idea is that the toes can hopefully be reattached after the giant box of car batteries falls off the catwalk directly onto your foot. This contrasts with the toes being smashed completely into a mangled glob of (again) human pizza, never to be salvaged.

…

Day One my crew was confronted by a series of dudes who had been working there for a few years. One chap who resembled “Weird Al” Yankovic was clearly the Don of the clique. Putting a stop to our clowning around, in a show of actively avoiding pleasantry, he boldly stated, “None of you guys will be here within six months”.

It was meant as an insult from a guy making about ten bucks an hour, who just decided he wanted to load trucks for the remainder of his life. Stealing our volleyball and kicking sand in our face, Weird Al projected his nuanced future forecasting based on repetition of witnessing his factory churn out failing widgets. The same quitters over and over again. In essence he was just that bored, and none of us stood out as remarkable to him. He and his gang sauntered on to the water cooler.

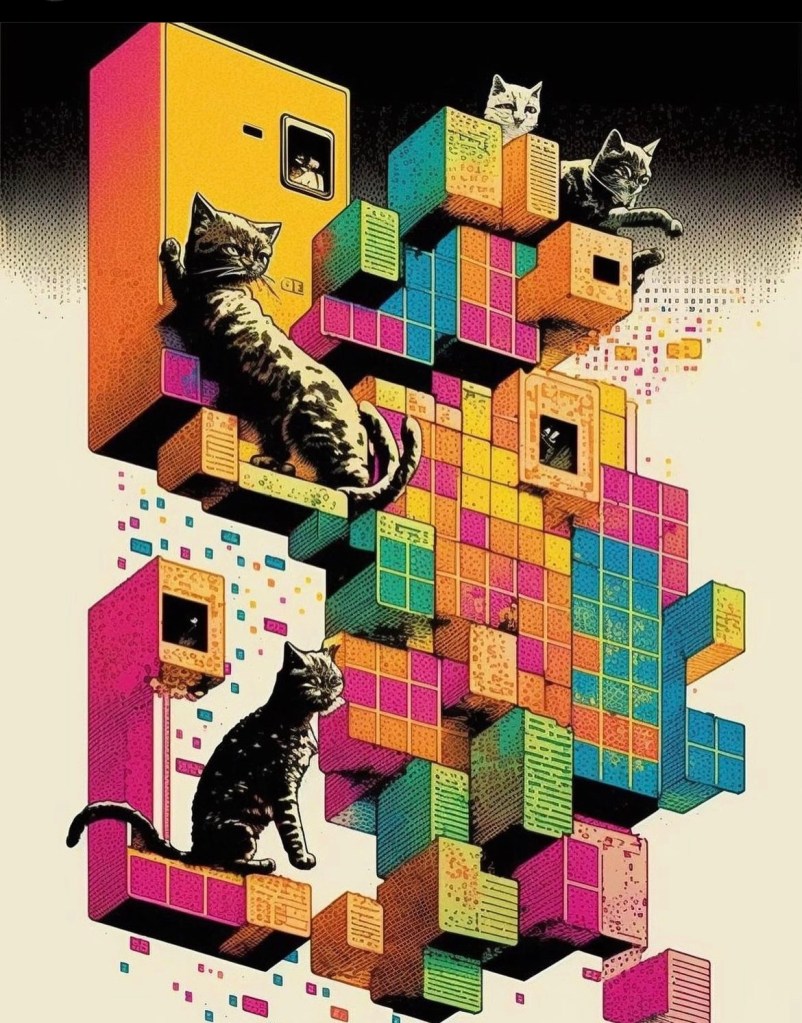

Some people couldn’t hack in the life-sized game of sweat-drenched, Fever Dream Tetris – fitting boxes from conveyors into trucks in ways efficiently enough to where they don’t fall over. Not like, once, but repeatedly for eight hours a day. There’s variation between the ones who couldn’t keep up and the ones who didn’t see a point. To Weird Al, the difference was negligible. He wasn’t wrong.

I took the “six months” threat from him as a compliment. I was relieved he saw something in me that wasn’t cut out for a life of mind-numbing boredom and repetition for a small fee. I knew from the outset that I didn’t want to be there for six weeks, let alone six months. If I could play it over again, I’d have walked back out the front door after six hours. Unless they’re paid adequately, loading boxes into semi-trucks is a level of demonstrable hell that no one deserves to be exposed to.

Some days that summer I’d get off work at 2 PM after the nonstop PTSD-inducing, exhausting physical labor, and I’d go home, shower and go directly to bed until 5 AM the next morning. I remember cleaning out my nose every day. It was just coated with black from inhaling dust and Caterpillar forklift exhaust. Ventilation would have been a luxury.

…

One time the boxes started coming down off the catwalk over the conveyor so quickly and relentlessly they began to topple over the side of the belt. I felt so stressed trying to load that truck properly with the backlog of boxes piling up all around me. Sweating and panicking, I remember I almost had some sort of mental episode. In my worldview at nineteen, I didn’t quite get that it didn’t matter. Sears would be profitable whether I lost mastery in my warped Tetris skills for a moment or not. Packages tumbling off the belts, crashing to the concrete floor. Me being powerless to stop it was a literal breaking point. I checked out.

I was in a satirical black comedy. Not unlike the characters in the film Office Space, which was released that very year, by the way. I was frustrated. Weary. (3)

Jesse would construct a daily chair out of boxes and sit on his carboard throne behind a partition of giant shrink wrap rolls and towering cardboard cubes. The voices told him it was okay. You had to stay hidden if you wanted a few minutes of a break. Feel like taking a seat on a stack of pallets for five minutes in clear view? Well guess who is scooting by on some sort of a golf cart mechanism to tell you to get the fuck up and go back to work. A fat guy, that’s who.

My friend Joe Quigley literally flung boxes of light bulbs so hard that he purposely shattered them in the back of the truck. I understood. Hearing the sounds of the muffled sparkly glass shards pop inside the packages was a tiny bit of satisfaction in a dull dreary den of sweat and heat. A small form of futile revenge in a world of no future. No money. I sold my Nintendo 64 in order to put gas in my tank and eat Taco Bell.

I recollect looking at the payphone over my lunch cooler in the breakroom, just wishing I had someone romantic to call and relay the stresses to. Not the girl I was dating, who I didn’t like, but you know…someone else.

…

During the work week, I took a nighttime welding course back at the community college to see if I could get interested in a trade. I don’t know. Maybe I could mesh art with mechanics and a lack of formal education and come out surviving? I was so unmoved I didn’t even finish the class. Big giant gloves and oxyacetylene tanks and a class full of country dudes who already knew how to weld. I hated it. I was so depressed.

In one more last-ditch effort to learn a trade, I helped a guy one weekend who used to build custom, high-end furniture for wealthy people. I wanted to follow in his steps, and I had a brief, glorious vision that he would carry me through. I took a trip with him up to Milwaukee in order to salvage some old telephone poles he planned to reclaim and build a table out of. The table would ultimately be commissioned by and built for David Schwimmer.

In a vacant, shadeless lot in the middle of the sweltering Milwaukee heat, I burned my Saturday helping this guy pull nails, staples and tacks out of giant telephone poles, cut them up and load them on to a giant flatbed by hand. (4)

Even as I write this, twenty-five years later – this was the single hardest day of manual work I have ever performed. I didn’t complain. But I never went back. Fuck that shit and fuck David Schwimmer. Fuck his luxury condo with hand-crafted reclaimed furniture. Fuckin Ross.

…

Not being driven, but also having no plan is a combo for the beginning of casually disregarding company protocol. Some days after the conveyor belt incident me and Samuel would just build a wall of boxes inside of the big box and then just toss other boxes over the wall of boxes. Not giving a shit if something broke. Sears definitely didn’t give a shit if we broke. Samuel, Jesse, Mark, Joe Quigley. The lot of us. A rag tag non-unionized blue-collar tribe of schlubs from the wrong side of the tracks.

“You see, Bob, it’s not that I’m lazy. It’s that I just don’t care. It’s a problem of motivation, alright? Now if I work my ass off and Initech ships a few extra units, I don’t see another dime, so where’s the motivation?”

I did go back to college a few years later. But for the window of the Summer of 1999, I just couldn’t see settling in for something I absolutely hated. Suicidal boredom of Survey of Art class or daily physical grunt work. Pick your poison. The fear instilled by capitalism-fueled culture created some heavy pressure on me in whitebread suburbia and it was a lot to balance. For most people, I guess.

During this time in life my friend who ultimately turned out to be a chode had been talking to me about a job that frankly just sounded too good to be true. He wanted me to come work with him in some sort of a vague construction role in some capacity [queue another Office Space reference].

It apparently didn’t require actual construction skills, and it was not a ton of hours. Frankly it sounded so easy (even if he was exaggerating), based on my current self-worth at the time, sadly I didn’t even know if I deserved something like that. I had been dismissing it for a few weeks because it was located roughly forty-five minutes away, and only fifty cents more per hour than what I made at Sears Warehouse.

I agreed to apply – and I took the job. At age nineteen it changed the entire course of my life and placed me within the industry in which I still reside to this day at age forty-four.

…

…

(1) Alex not only finished the art program, but he is now a fully functional adult!

(2) This is not a jab at social work, which happens to be a very noble profession. This is a jab at myself for assuming that a master’s degree in anything automatically leads to maximum wealth, and also that anyone might be pursuing higher education with intent on performing safety net obligations to an anxiety ridden dope like me.

(3) SLS and also K-Mart warehouse were local catch-alls for dudes like me who had no clear path and somehow just needed more nudging toward a trade or a college education. Five other friends of mine worked for Sears as well, either during my tenure, in other departments, or directly after I had left. Some specific horror stories exist, but one stands out from my friend Adam who somehow got stuck working there in the winter.

He said some days you could spit on the floor, and the saliva would freeze instantaneously. He also told me they would use cardboard from boxes as dividers to build barriers around the extension lamps that were used to look into the trailer beds. The little protective hut with the lamps (not designed to generate heat, mind you) would produce enough warmth to stave off freezebite.

(4) The guy, Dave Jenson, did absolutely brilliant work and he was very kind for offering to take me on as a sorcerer’s apprentice in the craft of magically transforming trash into treasure. This entire narrative is only written from the vantage point of me at age nineteen, funneling myself back to that pre-coffee drinking era filled with ignorance and oblivion, donuts and acne.

I picked orders and sometimes loaded or unloaded trucks at the Kmart Warehouse in 2003-2004. I lasted just over a year, so I got to experience all of the seasons inside a trailer. I left the job after developing carpal tunnel which has caused me pain for the rest of my life.

LikeLike

Sears no longer exists. You are still here. Win win for you.

LikeLike