Work-Life Composition, Saga No.: 7

[A Dissertation on My First Role in Construction Materials Testing]

September 1999, through September 11th 2001

I got a call from… a voice.

Over the black cordless landline, the apparition turned out to be Stu, the manager of a construction materials testing consulting firm. At age nineteen I stood in my dark basement bedroom in my parents’ place. Dreary from a nap after a relentless stint of loading trucks for eight hours, not even understanding who the phone call was from.

I didn’t even know the name of the company I had applied to. My friend at the time just had me fill out an application on a sheet of paper and I didn’t even inquire much as I handed it back to him. All I knew was that I was miserable at my current job.

“Testing?” At that moment, I thought it was a sketchy call from the marketer in a temporary storefront of Northfield Square Mall where I had recently been paid five dollars to fill out a survey. Was that some sort of “test” I took in that vacant mall corridor? The vortex of confusion took me a second to climb through. I swear I almost left Stu in a dial tone stalemate.

I’m sure Stu felt odd that I didn’t really know who I was even talking to. But he gave me a shot. On the monumental scale relative only to my feeble existence, accepting that telephone call, and not hanging up – changed my life. It would place me in the industry I still call home at age forty-five.

No interview and no meeting. Stu told me over the phone that I could start as soon as I was available.

Obviously, the only requisite was a pulse, a driver’s license, and probably a high school diploma, but I didn’t ask. Either way that trifecta was all I had to offer. It was very strange, and like my friend Dereck who got a job selling Kut-Co knives door-to-door, I figured I’d soon discover the catch.

After previously dropping out of art school, I put in a one-week notice at the verified hellscape wasteland known only as Sears Logistics Center. I only put in a one-week notice because seriously, fuck those guys.

With hopes marginally raised, in September 1999, I hopped in my ’93 Nissan Sentra. I drove up to start my $8.50 an hour job at some do-or-die blurry notion in Tinley Park as a construction materials tester.

The laboratory was located at 167th Street & Oak Park Ave, adjacent a 7-Eleven and connected to the back of an out-of-business video rental store. The first thing I noticed as I entered the lab that first day, was a wall coated with 1990s movies posters. I would soon keep the trend of sneaking back into the abandoned video store to secure the moldy, sun-bleached paraphernalia. Marketing for films like Beverly Hills Ninja and Liar Liar hand-stamped the video store’s closure at 1997.

My first week there, this dude Lucio was banked out cold in the lab. Just sitting, leaning up against the wall snoozing at 9 AM. Clearly, he was not afraid to do this, and that foreign, albeit comfortable principle began to instantly seep in. One manager Dave Fox came into the lab, looked at Lucio, then looked at me.

“Hey um, whenever Lucio wakes up, tell him to come talk to me.”

My mind was blown by that. Not only did Lucio not get into trouble, but the manager just let him finish his nap. One full grown man respecting the sleep schedule of another full grown man.

The job was a Goldilocks Zone for me. A perfect blend of ease, diligence, complexity, re-learning algebra, and downtime. I got myself somewhat removed from the Kankakee area and I got to experience the city and other counties. I eventually got to map out in my head, highways, interstates, and tollways. Exposure Therapy taught me other towns’ used record stores and fast-food locations. I learned directions, which way North was, and I got to figure out the City of Chicago grid system numbering layout.

Dave Fox took me to Applebees for lunch. It was nice.

We would have regular card games in the lab, especially on rainy days. Not like real cards but mainly Phase 10 and UNO. I couldn’t believe that management didn’t seem to mind, but I came to find that the low pay was worth it to them. Especially since we’d get any prevalent work finished before sitting down to play.

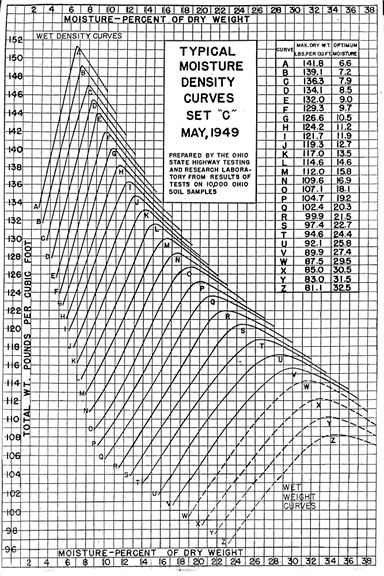

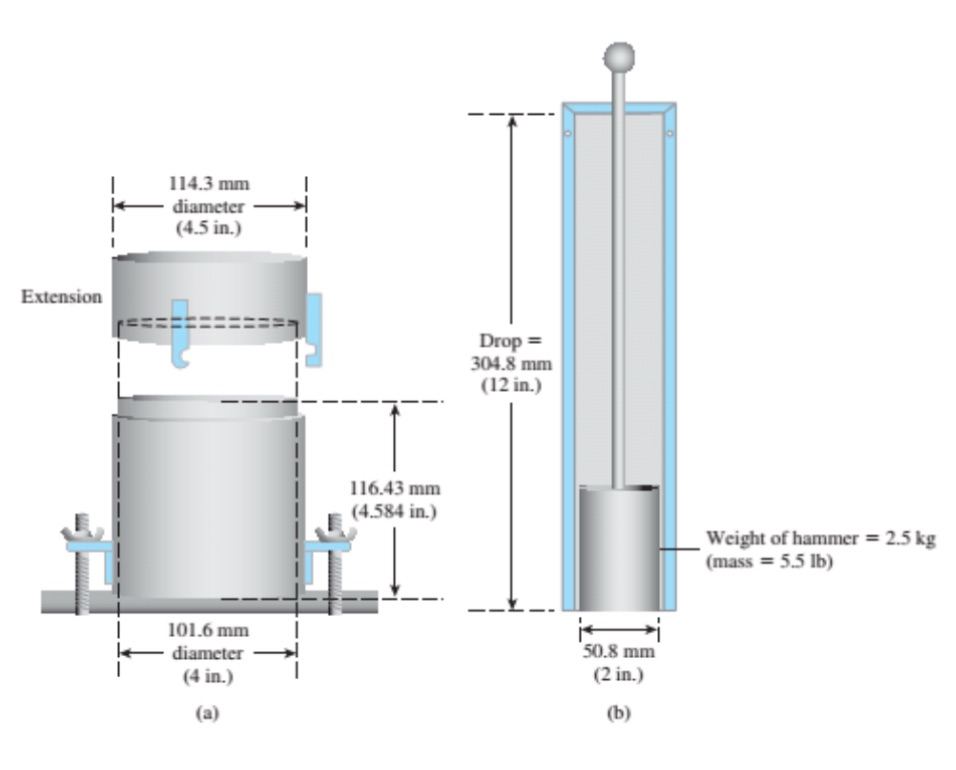

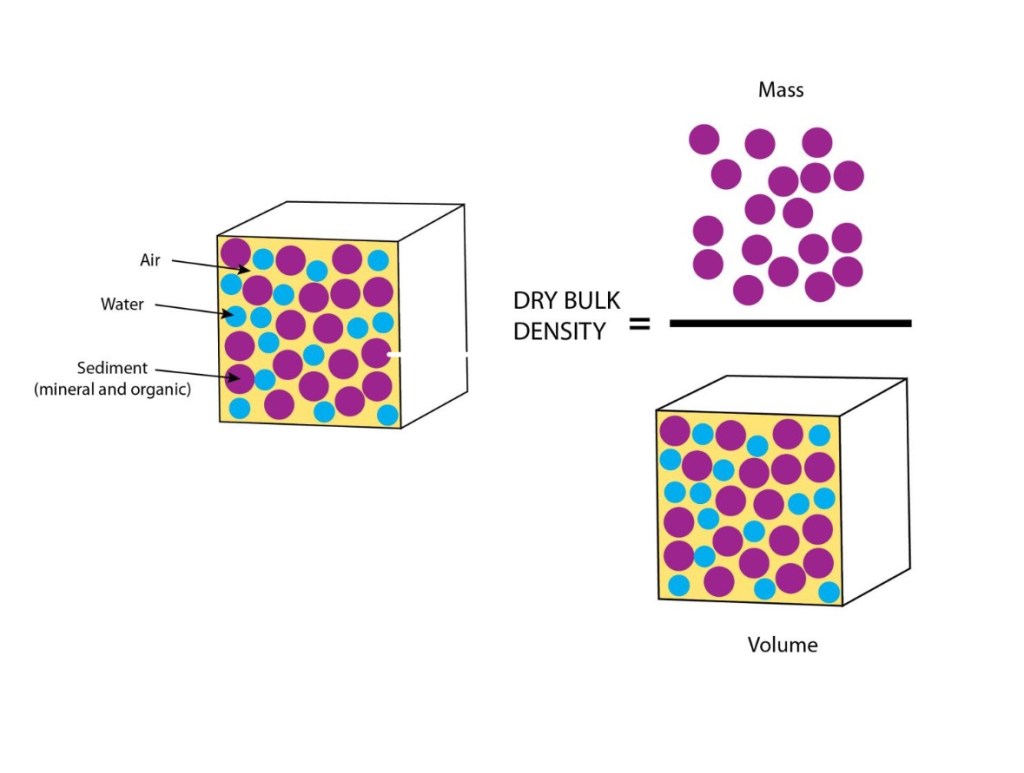

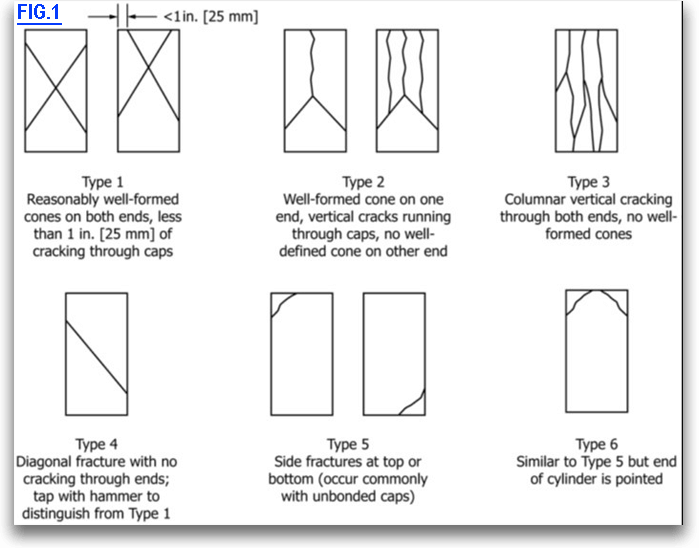

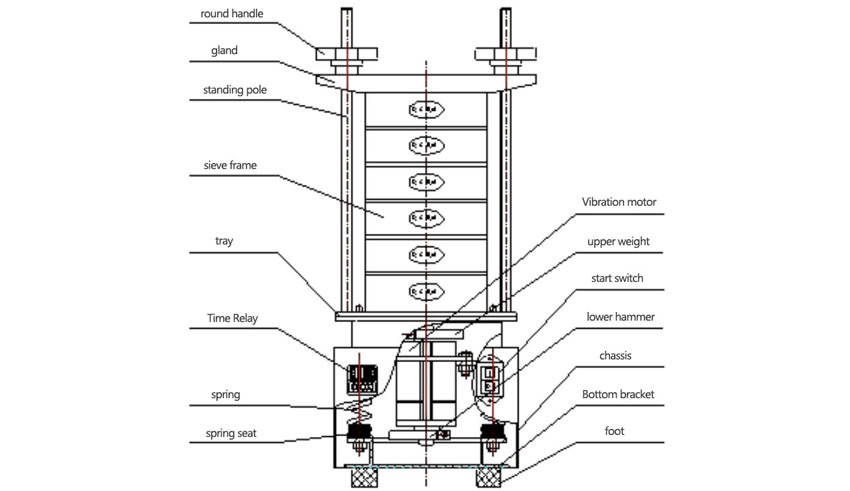

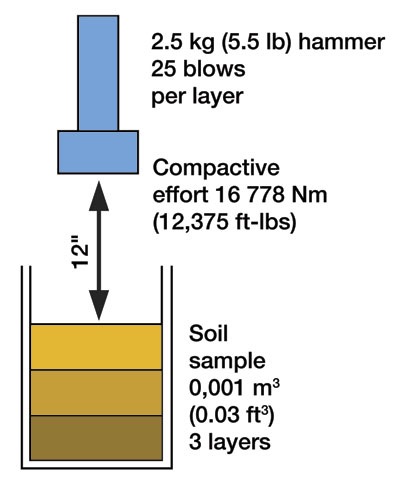

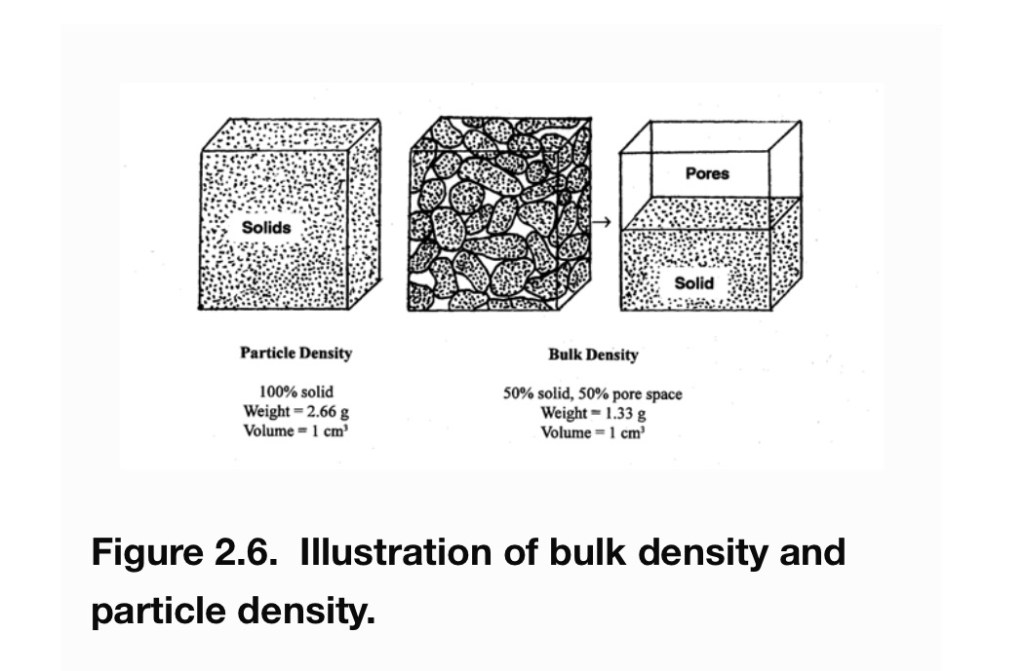

If the firm didn’t have anything for us to do, they remained profitable based on how much they charged for us to be on a job site and how much they billed for breaking concrete strength cylinders and running soil proctors (I guess). This is the only formula that makes sense to me. When there wasn’t any work going on, like in the winter, they must’ve decided it was not viable to send us home or lay us off due to the risk of losing the labor or even lowering morale. (1)

But we could go home if we wanted. They’d even pay us two hours just for showing up, if we decided to check out and head directly back to bed during a rainy day. Oddly it became a strange balance some days of forcing myself to sit there and do nothing with a space heater between my feet, versus going home and not being paid as much.

Some days after breaking up a clay proctor sample for drying, I’d walked over to 7-Eleven for lunch. Strange tubular “meat” items from those roller things, or a pig trough of nachos: a plastic tray of chips loaded with coagulated salsa, stale jalapenos and onions from the disgusting open air mini buffet. After I avoided the initial plug of dried liquid cheese, I’d coat those blue corn chips in viscous yellow matter, only to top it off with fluid chili from a dispenser. Chemical makeup of that chili? Unknown.

…

In the scheme of things my role was to be Quality Control for material placement on various, privately funded construction sites. Checking density on asphalt parking lots for big box consumer places like Darvin Furniture, and testing concrete for floor slabs at dark, cavernous, forklift exhaust-filled places like Mack Truck in Bolingbrook.

Handwritten field reports on carbon copy paper in triplicate, pagers, and a cardboard honor-system candy box.

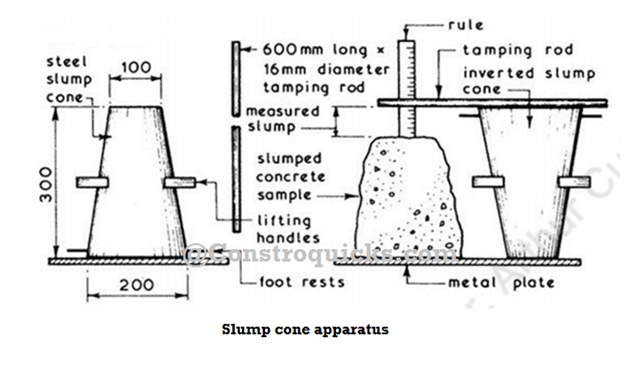

The first site I ever went to on my own was for testing the quality of concrete for curb at a new Heritage Bank building in Orland Park. I felt a sense of pride walking around on that job site under a clear blue sky, rubber mallet and strike-off bar neatly rinsed in my five-gallon plastic bucket of water.

The laidback-ness soon weaned a bit when the company realized I was able to show up on time, which happened to be the main requirement of the role. They started to toss me out on major projects:

Burlington Northern Santa Fe, an enormous rail yard on the south side of Chicago, with twisting makeshift driving lanes, set up around the internal construction sites. I do not remember taking any safety training, but I do remember the first thing the PM, Bill Kurts told me: “Bigger vehicles get the right of way. Watch out. See that trailer bed? One guy drove in to one of those and got decapitated.”

While sitting in the work truck one time at the rail yard, this laborer came over, stuck his head in my window and spoke between twisted yellow teeth, “I see you guys sittin’ here every day. Ya’ll young and ya’ll got some good jobs!”

I’ll never forget that feeling. I had a good job? Well. I guess compared to that laborer rocking a shovel.

I worked a few weeks at Argonne National Laboratory, which houses the world’s biggest Hadron Collider in the middle of a forest surrounded by white deer. Don’t worry, the deer just don’t have any pigment and they all just somehow live there, and nowhere else. It’s not because they drink radioactive water from local streams, and neutrino hydrogen bubbles funneling off the nuclear particle accelerator.

The white deer are striking. They are an irreplaceable memory in my databank.

Anyway, I was virtually untrained in any type of heavy paving processes, and at age nineteen, along with my severe lack of general communication skills and an utter nonexistence of confidence, I was a combination of calamity.

I was forced to process all of this over time… which was good. My company handed me a green toy hardhat and a slump cone and printed out a paper map of directions on how to get to the sites by 6 AM. Armed with my pager and a toll-free number, if I was confused or if I got lost, I’d call Stu from the nearest payphone.

“Well…”

I was never told what to do if something went wrong or if I got a failing field test. I got yelled at for touching a stringline at Ogden Yards when they were trying to pave some sort of roadway for train wheel truing. I got corrected by an annoyed, grammar-astute foreman:

“You don’t pour asphalt! You lay asphalt! You pour concrete, dip shit!”

It took years for me to learn the language, and frankly the more duties I take on, I’m still learning it.

…

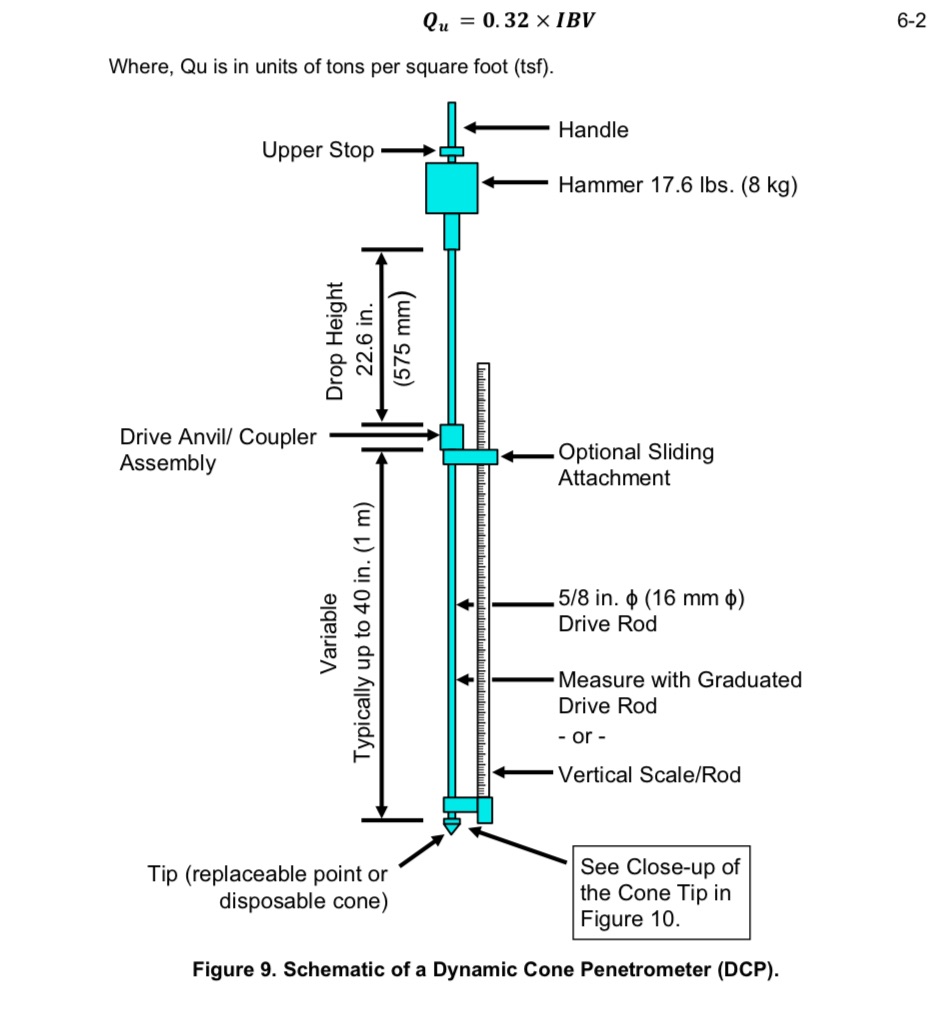

I have flashbacks of trying to check the bearing capacity on footings of an elevator shaft with a pocket penetrometer for some large building in Bronzeville. The soil was mud. I wouldn’t think it would support a human being let alone an elevator full of human beings. The bearing was 0.0. I remember telling them it looked… not great. The workers shrugged. Then I shrugged. Then I awkwardly left.

I never heard anything else about it, other than in the echoed screams of people falling to their death in my panicked nightmares. I just didn’t grasp that they were having some untrained kid inform them that they needed to fix something.

Why would they have a goofy teenager test bearing capacity on their elevator shaft footing? Why would they have someone test an elevator shaft footing that was made of mud in the first place? A few months prior I was sleeping in Survey of Art class wearing a Christian ska band tee shirt.

Not only was I not a professional engineer, or old enough to be one, or even on that pathway – but I wasn’t a good enough actor to even play one in a high school drama. Critical thinking skills hadn’t been fully uploaded and problem solving wasn’t yet a major part of my life. Loading trucks for a living was always in my periphery. Not only was I completely unprepared, but the internet and smart phones didn’t exist so I couldn’t even pretend.

Hopefully someone qualified made a call before they constructed an elevator on a base with zero stability.

Anxious fears linked to my previous job at Sears Warehouse – boxes falling off of conveyors en masse and not knowing what I’m potentially getting in trouble for. Fears of going to prison or being sued for people falling to their demise in an elevator that was built on goop. Everything tied back to me not telling them they needed to fix it. Not being able to know how to fix it. That sort of thing worked itself out as I learned more and more exactly what I was responsible for (i.e.; usually not much for my tenure there, really).

But nothing could better represent my time that first year testing materials than this:

My initial experience being flung out on an asphalt job was when they were placing surface for a subdivision. I remember arriving after they had been paving for hours and hours. I can’t recall why I was so late, but I’m absolutely positive my boss fell asleep at his desk while playing solitaire and forgot to tell me about the job.

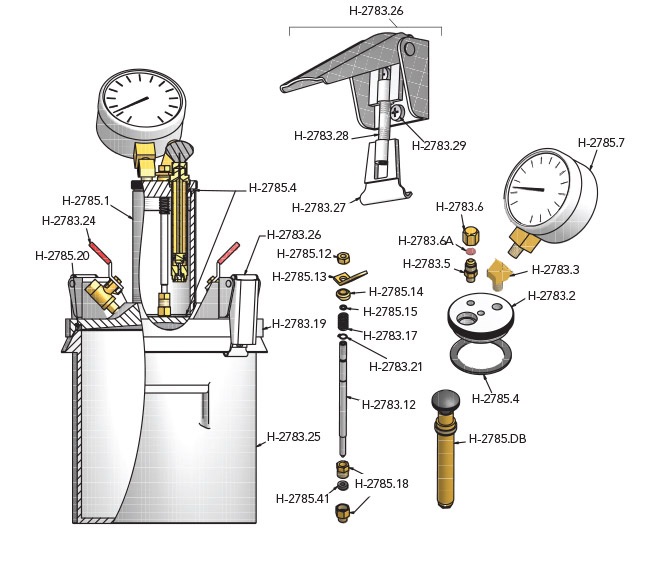

I showed up to test the density with the nuc gauge, and everywhere I tested was failing.

Frantically moving the thing around and pushing the button over and over. I didn’t know how to cheat by back calculating. I wasn’t aware that I could index the rod, meaning I could situate the nuclear bead in a way where it was reading the lead casing, which is obviously denser than a street.(2)

I couldn’t yet comprehend that if I set the gauge in a more “dense-looking” spot, I could get higher results. Since the tool reads air voids and gives you a weight, it’s compared against a lab standard value. If you set the gauge on an oily area, the density will read higher even if it’s not representative of the lab test.

Some dude (the Superintendent I would later find out) came over to ask how the density was. I told him it was failing. Me, having no idea what to do or how to be proactive, or that I even had any semblance of a duty to be proactive at the time, I just assumed the guy would shrug it off and walk away like the elevator shaft guys did.

The nameless functionary, who got me the job by randomly setting this ball into motion, who the company relied on to train me, implied that all we did was sit in our truck and report results. My mindset was molded that, at our pay scale, we “didn’t have to do anything else”.

The Super started freaking out. Literally screaming at me about how the mix was horseshit, and they would have to tear it all out, and he was completely baffled that I would allow them to keep paving all day with failing asphalt. At the very least it seemed to click at that point that I probably “needed to do something else”.

I didn’t know if it was better or worse that I had only just shown up and hadn’t been there all day stressing about failing density. Either way a Frank Brisali motherfucker was yelling at me in front of a bunch of other big ass construction men with shovels, and I don’t know that I’ve felt more intimidated in my life up to that point.

I wasn’t shown what to do or even taught the proper terminology. He asked me what the temperature of the asphalt was. Of course, I didn’t know. I didn’t know because I didn’t check it. I also didn’t even have a thermometer with me so I couldn’t check it even if I knew I was supposed to. I hazily remembered someone saying that hot asphalt was supposed to be… either three hundred degrees or three thousand degrees.

It might as well have been thirty thousand degrees because I paid so little attention during school, I couldn’t have told you the difference at the time between three hundred and three thousand degrees. Relatively speaking I had no basis to understand how hot asphalt was – at least in that split second, without having any time to analyze. (3)

Again, I wasn’t the most attentive to details regarding science class as a teen. I was more interested in writing poetry and counting down the minutes before lunch.

So, I told him it was “three”, just hoping he’d understand it was either basically three hundred or three thousand, whichever was more right. Then I could sneak away and figure out what it should be. I certainly wasn’t going to tell him I didn’t even have a thermometer with me in the first place (though looking back, that would have been a better option).

“Three?… Three-what?”, the Super asked.

So, I took a fifty-fifty shot:

“Three thousand. Three thousand degrees”, I told him in decidedly, unwavering confidence.

“Three thousand degrees”, he repeated.

He just walked away.

I literally still did not know if that was an acceptable answer or if he was just speechless in the knowledge that I was a complete buffoon.

It was necessarily one or the other, and I at least knew that.

I’d soon later figure out which.

…

Dave Fox sent me during those first few weeks to pick up a five-gallon bucket of soil for a lab sample. He asked me, “do you know TJ Lambert?”

I was so confused about why he was asking me if I knew this person TJ Lambert who I had just graduated high school with one year prior, and who had seriously dated a good friend of mine for a few years. I replied sheepishly, “…umm…yeah.”

Sifting through the star charts of my brain, within one second, I guess I just thought he had seen Manteno High School on my job application and connected it to TJ Lambert who he somehow knew went to Manteno, and also somehow knew was working on this particular jobsite? Was she actively pursuing construction management work while she was in high school and I never knew?

He seemed so confident in asking, it didn’t feel like he was just randomly inquiring if I knew some different person by the same name. And now, after I confirmed, he officially thought I knew what he was talking about.

Either way it happened so quickly I didn’t have time to dig. I arrived on the jobsite seriously looking for my longtime acquaintance, TJ Lambert to hop out of a truck or something. I did notice the equipment with “TJ Lambrecht” marked on the sides and I instantly clicked it. TJ Lambrecht, I came to find, was a construction contractor who specialized in mass earthwork.

I really don’t think I was that slow, mentally. I mean look, if I was, I still would be. I just need some god damn data sometimes, man. Just give me the info; it’s all I’ve ever asked. I truly just believe I was tossed into an even more real-world role than loading semi-trucks and cooking pizza at Aurelios.

The guy just assumed I might know a major local contractor by name. But I was still just marginally a legal adult, and until then my entire universe, at least socially and work-related was centered and isolated around Kankakee County or directly with family or church.

Most kids I went to high school with were only going into their second year at a university, learning critical thinking in libraries, expanding their analytical processes, and formulating their social lives at parties. I was injected into the mix at $8.50 an hour running slump tests and listening to Jerky Boys cassette tapes over and over ad nauseum with fifty-year-old divorcees.

…

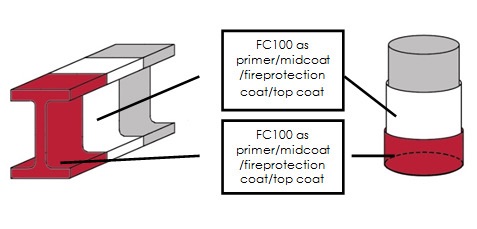

Air entrainment, mortar cubes, grout prisms, soil borings, fireproofing, static cone penetrometers.

I pissed this one tech off by defacing his weightlifting magazine with mustaches and unibrows. I recall telling him “I didn’t do it” after he confronted me. There was another guy, Kieth Johnson. I studiously changed all of his handwritten reports to “Keith’s Johnson”.

A female technician who was a college intern – I remember that I was assigned to take her to a site for training. I showered the morning-of (which I never routinely did), and I got my car detailed, since to me, this was most definitely a date.

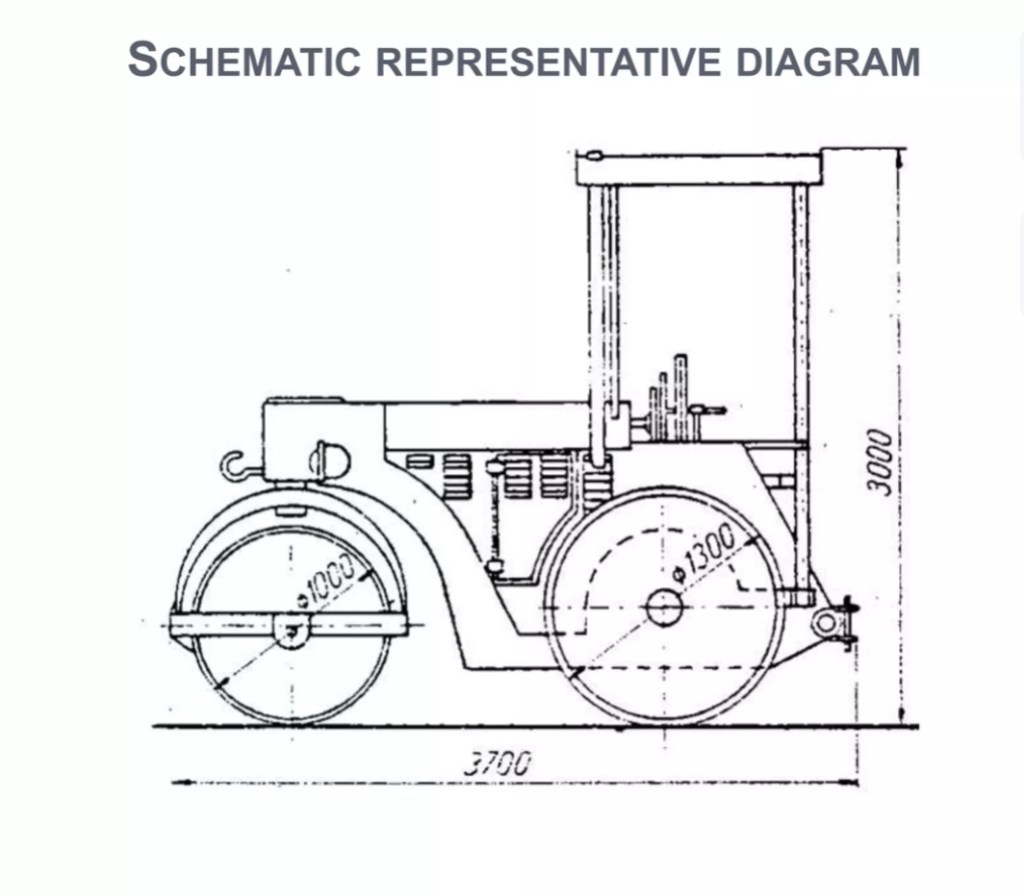

My favorite type of project was mass earthwork grading. I’d be on the same project for weeks in the summer, just waiting all day for them to move soil into building pads so I could jump out of my truck and do a few density tests with the nuclear gauge. I did this frequently for hours and hours. Twelve-hour days sometimes, making that mad Oliver Twist.

It was a time before texting, or smart phones. I’d begin to fall into my own world inside the universe of urban sprawl clearing for grade, down to virgin earth surrounded by giant mounds of clay ready to be spread and compacted.

I don’t think I was quite into reading books yet, but I would write a lot. I taught myself how to play drums in that old Dodge Ram beater pickup. Figuring out patterns and rhythmic arrangements, I’d tap along all day to R&B songs on FM radio until I figured it out. Janet Jackson, Sisqo, 3LW, 702. You know, the hits.

Sitting there for so long, I actually had to make a mental point to not let my left arm get sunburnt while the right arm stayed ghostly pale.

On the actual work end, the solutions I found were easy. If the soil wasn’t compact enough, I’d just tell them to run it over again with the sheepsfoot compactor, and I’d retest until it passed. If they beat it so much that it couldn’t possibly compact anymore and it was still failing even after I applied a correction factor, I’d just note “maximum compactive effort was achieved”. Done and done. Then I’d go sit in my truck again for two more hours and write rap lyrics.

To this day when I get the scent of clay in the open air, I’m tossed back to these long summer days, collecting duckets, smoking Black ‘n Milds, and eating Salsa Verde Doritos.

…

In February 2000, we loaded up the cylinder break machine and moved our office and lab to Mokena at 183rd Street and 80th Ave. Me and Horatio, driving from one lab to the other in a box truck listening to Third Eye Blind on the radio. Over the span of those first six months, most of the other technicians I met had moved on to better paying roles. Horatio went to be a roofer. Others, like Lucio, went to go work QC for contractors. Christos Giannopoulos quit to start his own lab in Greece.

By that Spring, we were (well really just the guy who got me the job was) able to get five of our pals jobs with us as materials testers at the company. At one point, including the OG named Jack, there were eight technicians in total. All eight of us were friends outside of work – playing in the same bands, all listening to the same music. Some of us even became roommates.

I remember that summer, thinking, as we would conduct our UNO tournaments – the prior summer I was in a specific form of capitalistic hell (4), but now I was just hanging out all day every day with my friends for a living. An initial pattern display of the juxtaposition from what life drains from you, into what tranquility the exact same life can lend… if you stay alive just long enough.

The Mural.

As more people came on board, Ziggy, A-Train, et al, we would plaster tiny pieces of magazines on a wall in the lab, slowly creating an ever-growing, gargantuan mural. These would necessarily be pictures of unattainable women torn out of Maxim Magazine. It was an homage to the movie poster wall from the original lab. Sheer liquid boredom on steroids, it was a form of nondestructive entertainment for a sizeable group of guys barely out of adolescence.

Stu must’ve walked by our giant mosaic of pictures at least one-hundred times, never saying anything about it. Obviously, we had been creating it while on the clock, and in a specific spirit of intentional unprofessionalism, pushing the bounds, it had clearly taken many, many hours to patch together.

The behemoth was spreading from the wall to over the stair banister, taking on a life of its own as we studiously taped a coated paperstock quilt of Destiny’s Child, Jessica Alba, and Jennifer Lopez.

An apex arrived one random day when Stu walked into the lab to inform us that someone was coming in from the corporate office. We needed to take the mural down. We were a bit dejected, yet we understood. We had gotten away with the abstract art piece for long enough as it was. We got paid for months to put it up, and we were paid to tear it all down.

Like children I think we needed boundaries, which were never set. If given enough time, the mural would have taken over the entire cavernous lab. Mathematically, why would it not? Frankly we got a laugh at how awkward the directive was. Stu with no eye contact was obviously just as bummed as see it go.

…

We graffitied up the shop table to where there was zero negative space among the Nazca Lines and encrypted geoglyphs. Every one of us listened to and conversed about Mancow’s Morning Madhouse on Q101 every single day of the work week as if it were a religion.

We would pull our cars into the lab just to wash them on the clock.

Joe and I spent a lot of time eating at Burrito Jalisco. Some rainy days I just wouldn’t come back to the office after lunch because I was so stuffed and groggy after eating a burrito the size of a baby. I’d leave Burrito Jalisco, head down 159th Street and come to the decision point. Head down 80th Ave back to the lab or just continue on home to sleep? The naps became well worth it to not go back to work those days. Until I saw my next paycheck, of course.

We brought in plush furniture from the garbage to sit on and literally armchair theorize on the best bands and the coolest cars. Debates about the most important things in life, before most of us had any accountability to anyone else on Earth.

One perpetual argument was about how and where our pay rates were actually allocated. If you spent ninety minutes during the workday at Threshold, the local record store perusing CDs, an album purchase would then pay for itself. The question was whether or not you had to actually be at the record store in order to offset the cost of the CD.

I was in the camp that decided you needed to have your full ninety minutes in the physical shop in order to effectively pay off the purchase. Others would chime in under the school that as long as you are simply not working, the CD would be paid for by itself. My line of reasoning would default to the fact that flipping through CDs was actually work. It was in fact an imperative part of my job.

We wore film badges that the firm would mail in to a laboratory every month in order to detect how much radiation we were absorbing from the nuclear gauges. This guy Craig took some vacation time, and I clipped his film badge to the antenna of my work truck in order to soak up the direct sunrays for a full week. Just like half the failing field test results we reported for building foundations – we never heard anything back.

Eventually, one by one, due to the high turnover rate based on low growth prospects and low pay, we would all go our separate ways. The Tinley Park branch party disbanded, and that clubhouse would close for good in 2008 due to the housing and commercial real estate recession.

The rest of us took different roles at other firms that paid marginally more, and began performing Agency work on projects for IDOT, CDOT, INDOT and the Tollway. I left that specific firm years before the testing portion of the construction industry would unionize.

That era of 2000 through mid-2001 was one of the best working experiences I could have ever hoped for. Nothing but the fondest memories of summers cruising back from a job site to see all my buddies just sitting at the table in the lab creating top ten lists of bands and rappers and actresses they were attracted to. Emo and Hardcore playing on the boombox while running proctors and breaking cylinders. Never seeing our boss Stu, but assuming he was in the next room eating popcorn out of a bowl with a spoon.

“Well…”

…

My final week at the company was the week of 9/11.

The morning of September 11th, 2001 I was on my way to a BNSF rail yard at Ogden & Cicero to test concrete. I was listening to my 2pac All Eyez on Me CD and was oblivious as to what was going on. I pulled into Cub Foods for something to eat (but please don’t ask why I went to a grocery store in the morning to get something to eat).

I’ll never forget in my hazy universe of naïveté, the cash register person’s now-iconic statement searing through like a hot box cutter:

“They gon’ mess around and start a war.”

I got back in my car and switched the CD player to Q101 to hear what Mancow had to report. Whatever was happening, I was positive he’d be commenting on. I don’t think I could have told you what the Twin Towers even were before that date. I definitely had never heard of the Taliban. When I heard the cast of that radio show screaming that this was “Armageddon” I knew that whatever the fuck was going on was about to pull me even further away from my artless, trustful state of world wonderment.

I remember working that full day. Cicero Yards isn’t too close to the downtown area, but I recall a sense of uncertainty based on the radio as well as construction workers on the job site. The question that morning was whether the Sears Tower, Chicago’s tallest symbol of capitalism, may be hit by a hijacked airplane. I know they evacuated the entire building. I wasn’t working near it, but I could physically see it from the South Side.

The most eerie feeling of working in the city on 9/11, especially being close to Midway, was the complete silence in the skies. All commercial flights to or from anywhere across the entire country were stopped as the airports came to a grinding halt. In Chicago you get so used to the noise of planes drifting through the sky overhead, when they vanished it created a vacuum of discomfort.

I drove home that night and watched all the footage on the television in our living room with my two roommates Chey and Roy. It’s amazing to me at this point in life that without cell phones I couldn’t even visualize what the massacre looked like until about ten hours after it actually happened, and I saw it on the TV.

At twenty-one, as a non-college student, I was the prime for army recruitment. We had heard rumors of a draft reinstatement, and I recall having conversations about it. Luckily it never came to that.

…

My last day at the company was a Saturday at BNSF Railyard. I finished preparing my cylinders of utility duct bank concrete (dyed red so future diggers might see it before completely tearing it up). I remember saying goodbye to Bill Kurtz, but I never saw Stu since I was dropping off my keys and equipment on a weekend.

I wasn’t fully sure if I should have left that company at that point. I gave up working with all of my friends for only a dollar or two more per hour. But my interest in growth was methodically considered. There was a charm to the easygoing nature of that company, but there was something in me that contained a bit of a motivator; I knew I had to cash in the trade-off of more intense work and more responsibility with the idea of at least the chance of moving upward.

…

(1) I’ll never forget the story I was told a few weeks in. Lucio and Christos Giannopoulos were driving in the company truck with a nuclear density gauge in the back on their way to a job site. The way Lucio described the event over a game of UNO, was that while on the interstate, Christos looked in the rearview mirror and exclaimed, “Oh sheet. The gate. It is open!”

The nuc gauge, which was supposed to be secured to the truck (not to mention the tail gate, which nobody bothered to close) had fallen out of the back of the vehicle at some point. “At some point” being perhaps the scariest notion here. This is not only an $8,000 piece of equipment, but it emoted radiation. If the thing got run over on a jobsite, the protocol was to shut down the project, mark off a fifty-foot perimeter and call the nuclear regulatory commission to retrieve it.

They did a U-Turn on I-57 and backtracked, gunning it at 90 miles per hour. They found it about a mile back, in Blue Island on 127th Street from before they had entered the Interstate. Luckily Someone had moved it to the median and it hadn’t been stolen or hit by a truck. They loaded it back on the pickup and never said a word to Stu.

(2) I don’t recommend this. All I’m really saying is that I could have just told the guy it was passing, and if he wanted to see the screen on the gauge as a form of proof (which he wouldn’t have), there were ways to lie. This was only for private work. I remember the Super calling out another in-house technician who would put magic mineral filler dust down on the surface and achieve passing results on the very same asphalt I was testing.

It was then I knew that testing asphalt for a subdivision would be one of the more easy gigs I could be rewarded in the future.

For agency projects like IDOT, CDOT or Tollway, the QC/QA program would be put in place as a checks and balances to attempt to offset any falsifying of results.

Learning the ways in which technicians cheat would in fact become a valuable card in my future deck in Materials Management.

(3) I wish I knew that the title of Ray Bradbury’s book Fahrenheit 451 was an allusion to the flashpoint of paper. I could have at least deduced that three-thousand-degree asphalt would instantly kill anyone even close to it, let alone standing directly on top of it. Again – I didn’t devote much energy to retaining data up to that time of my life.

(4) Originally this essay started with my experience in loading trucks at Sears Warehouse. I separated the essays and the Sears Warehouse one is under “Life in Fever Dream Tetris – Saga No. 6”.